You might have seen webhooks mentioned in your apps' settings and wondered if they're something you should use. The answer, in a nutshell, is probably yes.

Webhooks are one way that apps can send automated messages or information to other apps. It's how PayPal tells your accounting app when your clients pay you, how Twilio routes phone calls to your number, and how WooCommerce can notify you about new orders in Slack.

They're a simple way your online accounts can "speak" to each other and get notified automatically when something new happens. In many cases, you'll need to know how to use webhooks if you want to automatically push data from one app to another.

Let's break it down, learn how to speak webhook, and get your favorite apps to talk to each other.

What Are Webhooks?

There are two ways your apps can communicate with each other to share information: polling and webhooks. As one of our customer champion's friends has explained it: Polling is like knocking on your friend’s door and asking if they have any sugar. Webhooks are like someone tossing a bag of sugar at your house whenever they buy some.

Webhooks are automated messages sent from apps when something happens. They have a message—or payload—and are sent to a unique URL—essentially the app's phone number or address.

They're much like SMS notifications. Say your bank sends you an SMS when you make a new purchase. You already told the bank your phone number, so they knew where to send the message. They type out "You just spent $10 at NewStore" and send it to your phone number +1-234-567-8900. Something happened at your bank, and you got a message about it. All is well.

Webhooks work the same way.

Take another look at our example message about a new order. Bob opened your store's website, added $10 of paper to his shopping cart, and checked out. Boom, something happened, and the app needs to tell you. Time for the webhook.

Wait: who's the app gonna call? For webhooks, you first need to tell the first app—your eCommerce store, in this case—the webhook URL of the app that needs the data.

Say you want to make an invoice for this new order. You'd first open your invoice app, make an invoice template, and copy its webhook URL—something like yourapp.com/data/12345. Then open your eCommerce store app, and add that URL to its webhook settings. That URL is your app's phone number, essentially. If another app pings that URL (or if you enter the URL in your browser's address bar), the app will notice.

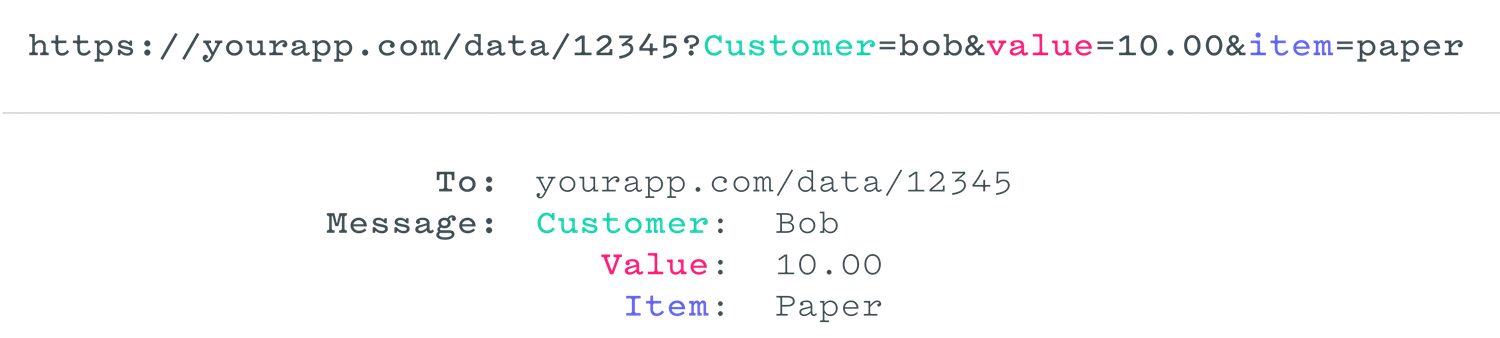

Ok. Back to the order. Your eCommerce store got the order and knows it needs to send the details to yourapp.com/data/12345. It then writes the order in a serialization format. The simplest is form-encoded, and your customer's order would look something like this:

Customer=bob&value=10.00&item=paper

Now you need to send the message. The simplest way to send data to a webhooks URL is with an HTTP GET request. Literally, that means to add the data to the URL and ping the URL (or enter it in your browser's address bar). The same way you can open Zapier's about page by typing /about after zapier.com, your apps can send messages to each other by tagging extra text with a question mark on the end of a website address. Here's the full GET request for our order:

https://yourapp.com/data/12345?Customer=bob&value=10.00&item=paper

Deep inside your invoice app, something dings and says "You've got mail!" and the app gets to work, making a new invoice for Bob's $10 paper order. That's webhooks in action.

Remember when you had to check your email to see if you had new messages—and how freeing push email was? That's what webhooks are for your apps. They don't have to check for new info anymore. Instead, when something happens, they can push the data to each other and not waste their time checking and waiting.

That's the simple version. Technically, webhooks are "user-defined callbacks made with HTTP" according to Jeff Lindsay, one of the first people to conceptualize webhooks. Webhooks are data and executable commands sent from one app to another over HTTP instead of through the command line in your computer, formatted in XML, JSON, or form-encoded serialization. They're called webhooks since they're software hooks—or functions that run when something happens—that work over the web. And they're typically secured through obscurity—each user of an application gets a unique, random URL to send webhook data to—though they can optionally be secured with a key or signature.

Webhooks typically are used to connect two different applications. When an event happens on the trigger application, it serializes data about that event and sends it to a webhook URL from the action application—the one you want to do something based on the data from the first application. The action application can then send a callback message, often with an HTTP status code like 302 to let the trigger application know if the data was received successfully or 404 if not.

Webhooks are similar to API—but simpler. An API is a full language for an app with functions or calls to add, edit, and retrieve data. The difference is, with an API, you have to do the work yourself. If you build an application that connects to another with an API, your application will need to have ways to ask the other app for new data when it needs it. Webhooks, on the other hand, are for one specific part of an app, and they're automated. You might have a webhook just for new contacts—and whenever a new contact is added, the application will push the data to the other application's webhooks URL automatically. It's a simple, one-to-one connection that runs automatically.

How to Use Webhooks

You know the lingo, understand how apps can message each other with webhooks, and can even figure out what the serialized data means. You speak webhook.

It's time to use it. The best way to make sure you understand how webhooks work is to test it out, try making your own webhooks, and see if they work. Or, you can jump ahead and just drop your webhook URL into an app to share data—after all, you don't have to know how to make webhooks to use them.

Here are the resources you need.

Test Webhooks with RequestBin and Hurl.it

The quickest way to learn is to experiment—and it's best to experiment with something you can't break. With webhooks, there are two great tools for that: RequestBin and Hurl.it.

RequestBin lets you create a webhooks URL and send data to it to see how it's recognized. Unfortunately, the original web app has been taken down, but you can install your own copy on Heroku in a few clicks or install the open source version of RequestBin on your own server. Or, you can run a copy of RequestBin from FullContact, or try a similar tool like Hookbin.

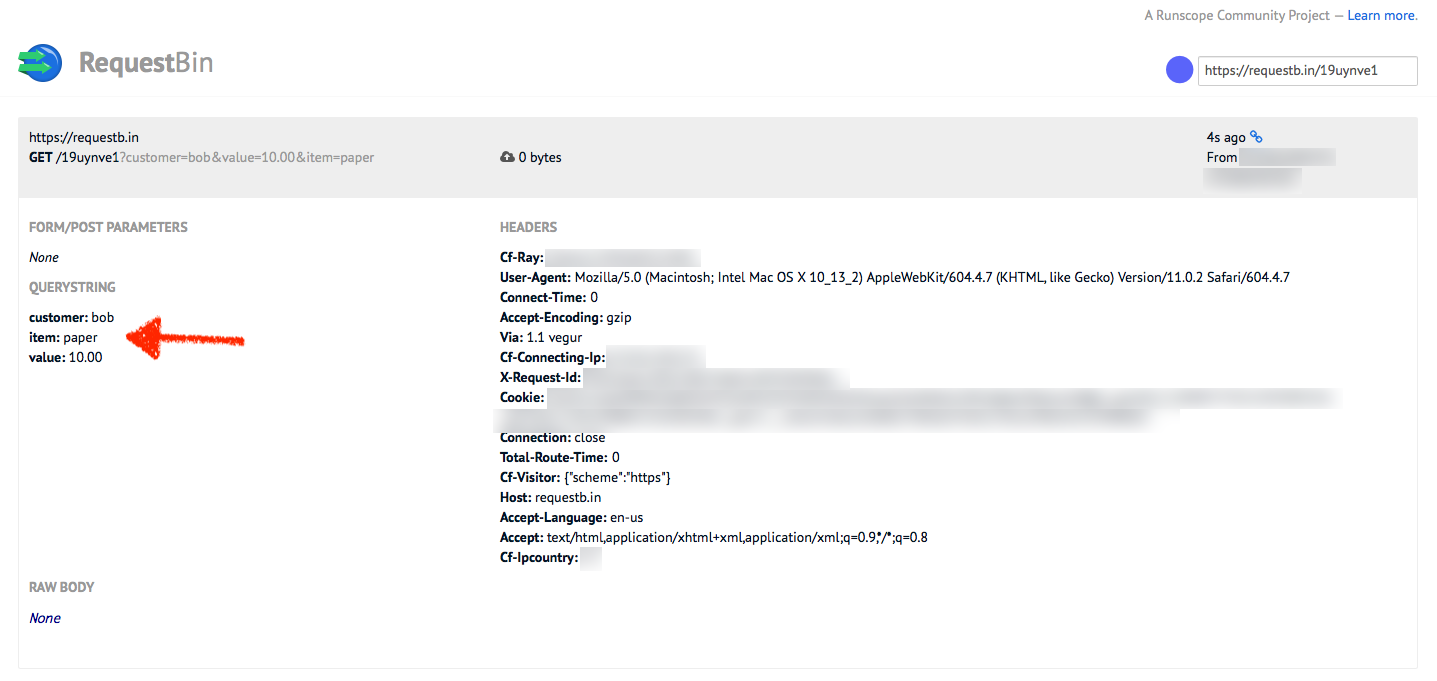

If you're using RequestBin, open the app and click Create a RequestBin, then copy the URL it gives you.

Now, serialize some data in form encoded style—or copy our example form copy above. Open a new tab, paste your RequestBin URL, add a ? to the end, then paste your serialized data. You'll end up with something like this:

https://yourdomain.com/19uynve1?customer=bob&value=10.00&item=paper

Press enter in your browser's address bar, and you'll get a simple message back: ok. Refresh your RequestBin tab, and you'll see the data listed on the left as in the screenshot above.

You can then try sending POST requests in Terminal or from your own app's code, if you'd like, using RequestBin's sample code. That's a bit more complex—but gives you a way to play with JSON or XML encoding, too.

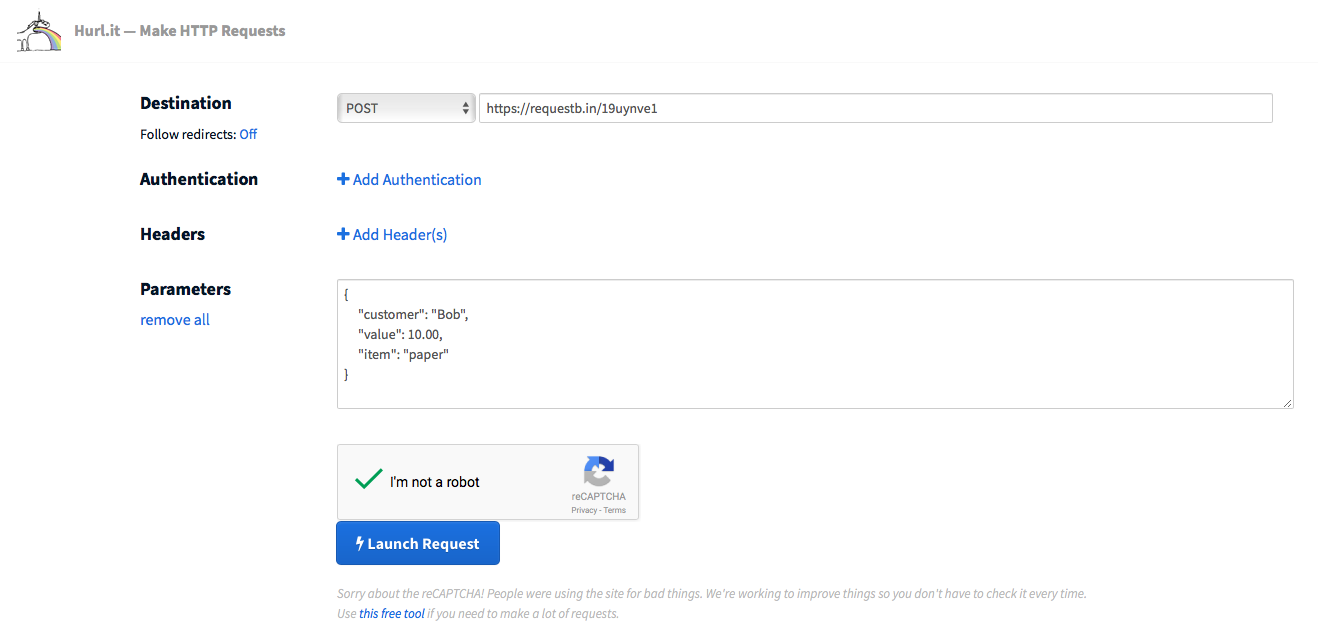

Or, use another app for that. RequestBin's companion app, Hurl.it, lets you make custom HTTP requests for an easy way to send customized data to a webhooks URL. Enter the URL, then choose the HTTP request method you want to use, and add the body data. That'll let you send far more detailed requests to your webhook URL without having to use more code.

Add Webhooks to Your Apps

Testing webhooks and serializing data by hand is tricky—as is copying and pasting data from your apps. Let's skip both, and just get our apps talking to each other.

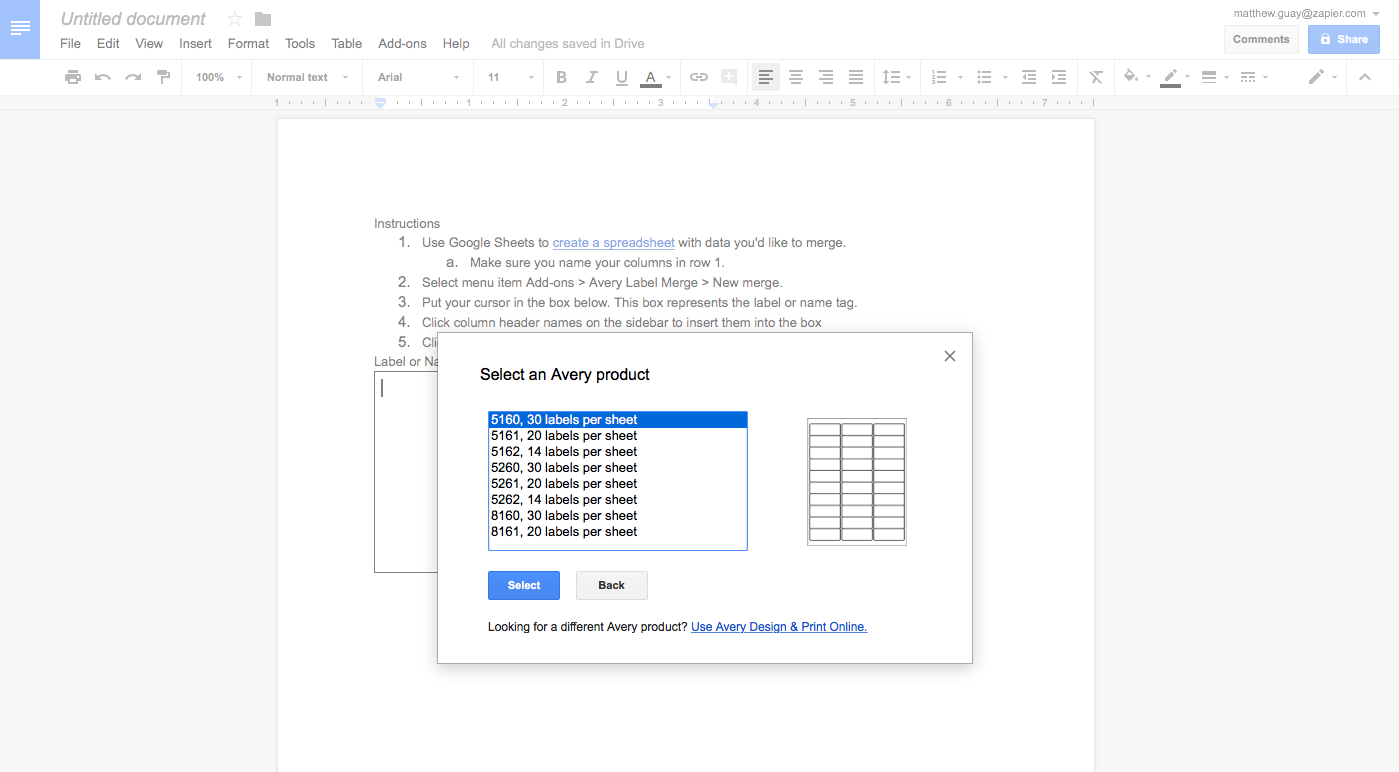

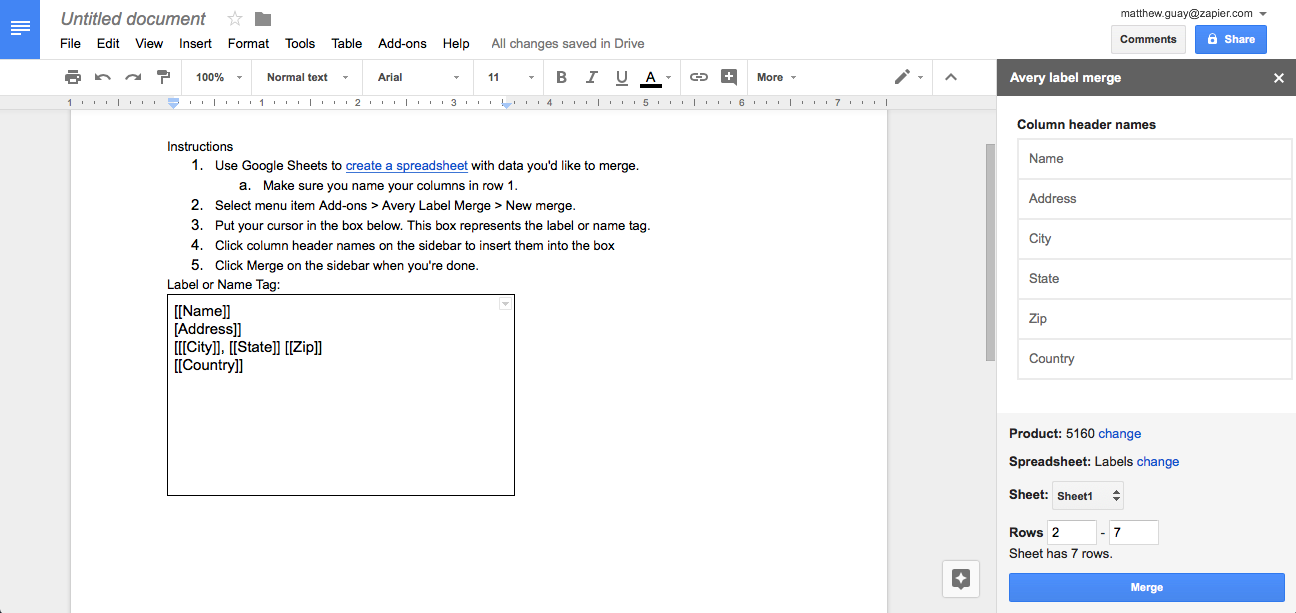

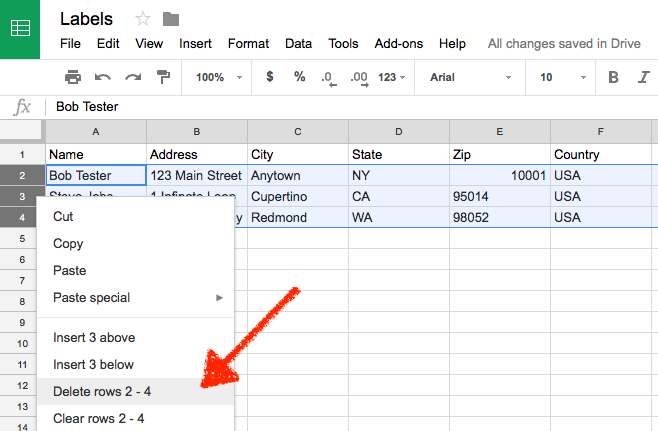

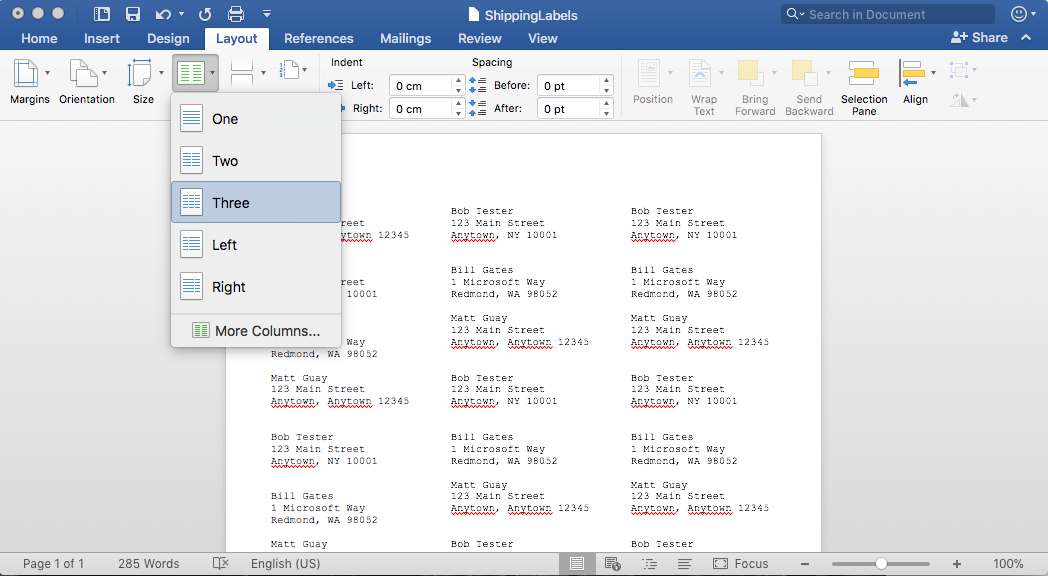

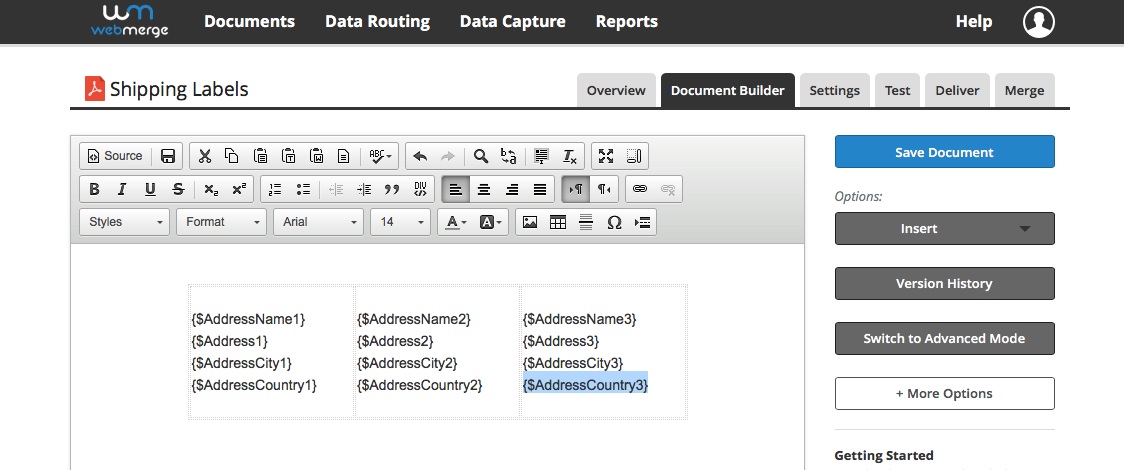

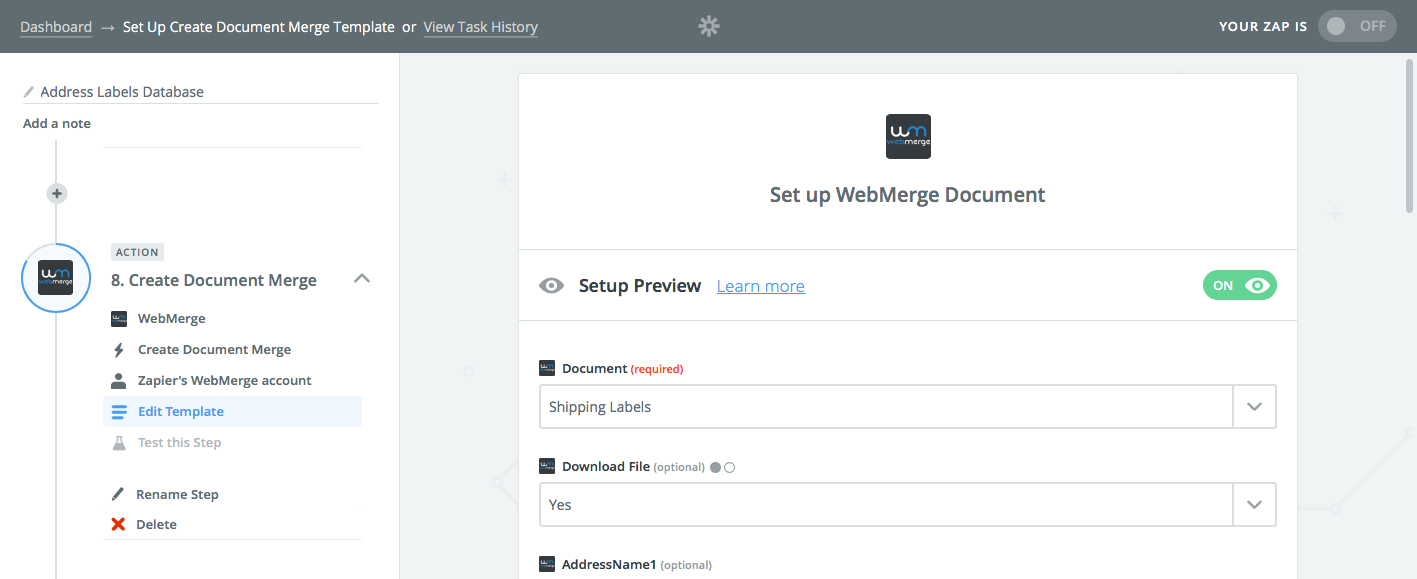

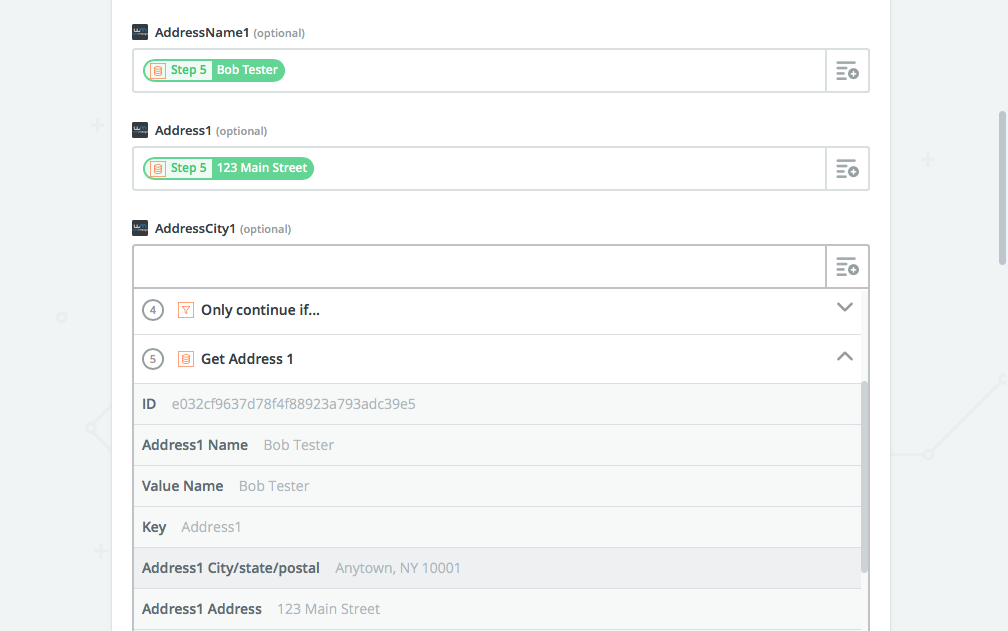

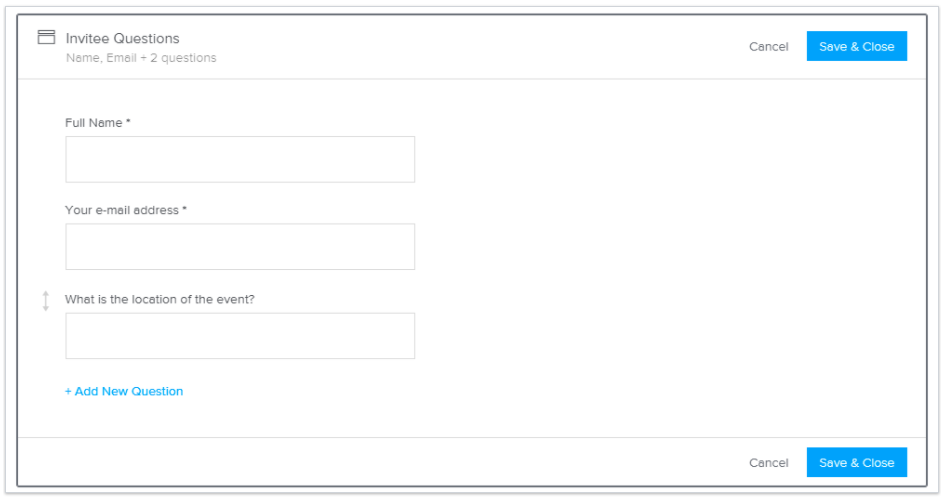

We're using WordPress-powered form tool Gravity Forms and document template-builder app WebMerge as the examples here—but the same general idea works in most other apps that support webhooks. Here's essentially what you need to do:

First, enable webhooks in your app if they're not already and open the webhooks settings (in Gravity Forms, for instance, you need to install an add-on; in Active Campaign or WooCommerce, you'll find webhooks under the app's default settings). Your app might have one set of webhook settings for the entire app—or, often, it'll have a specific webhook for each form, document, or other items the app maintains.

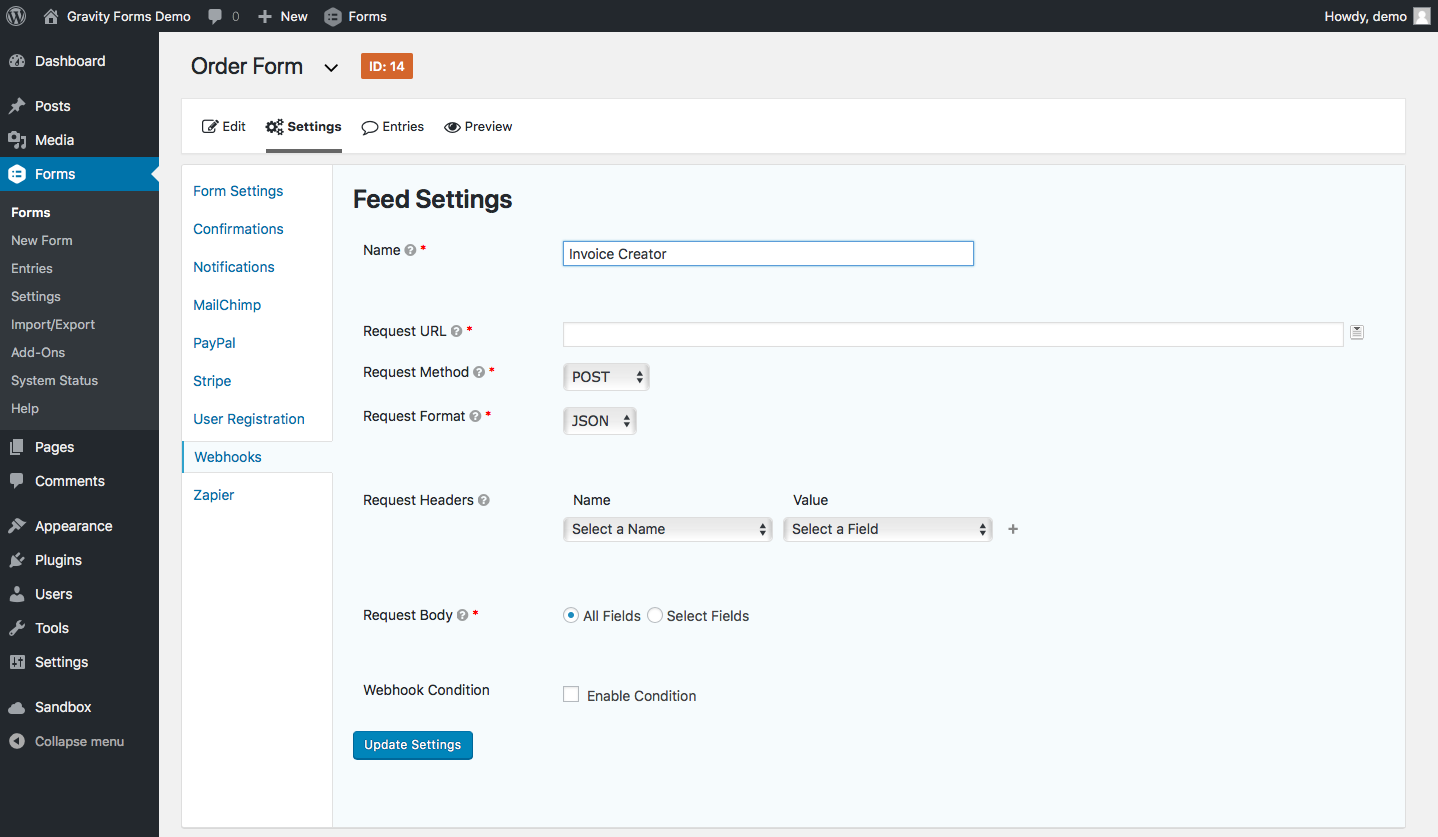

In Gravity Forms, we'll open the Webhooks settings under the form we want to use. That gives us a URL field and options to specify the webhook HTTP request method.

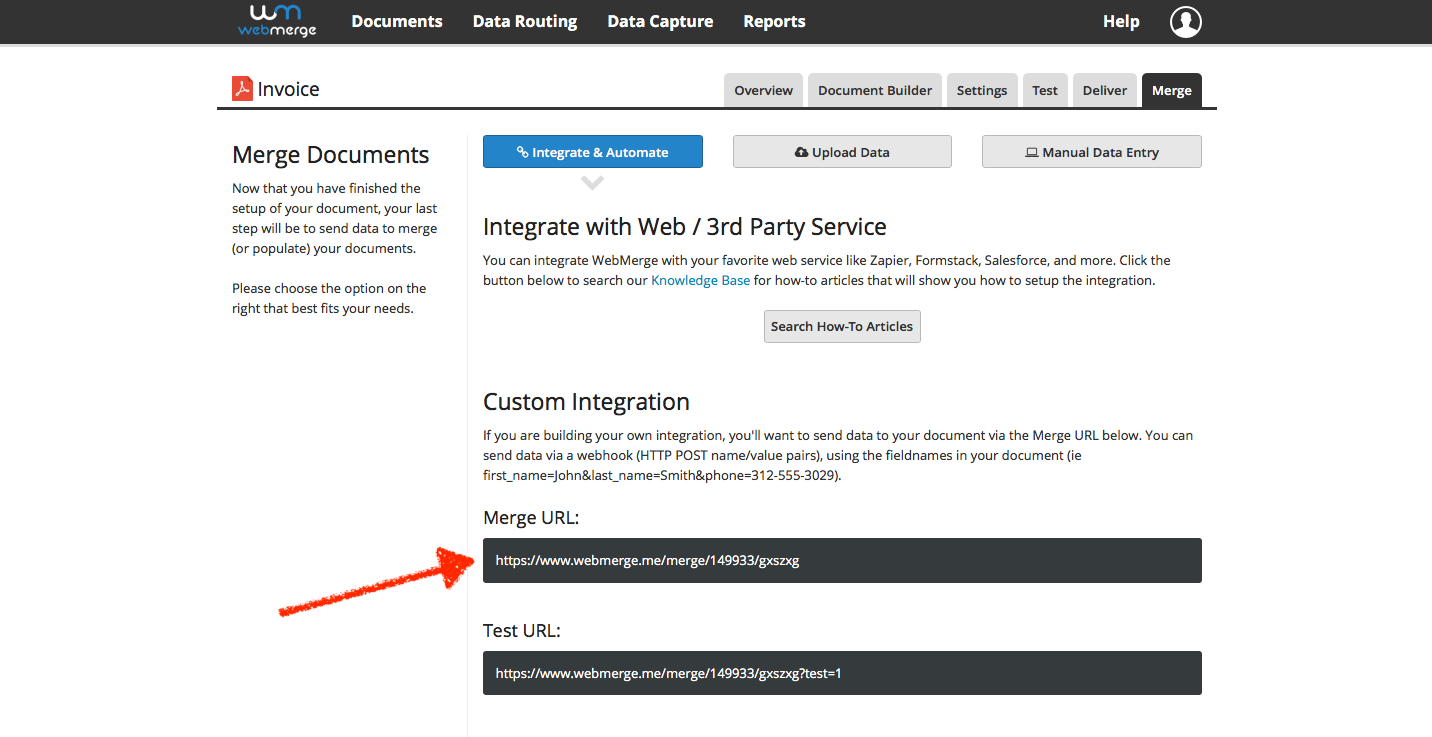

Now let's get that URL from the app that will receive the data—WebMerge, in this case. In WebMerge, each document has its own "merge URL"—and it wants the data in form encoded serialization, as you can tell from the ampersands in the example data. Copy the merge URL—or whatever URL your app offers, as it may have a different name.

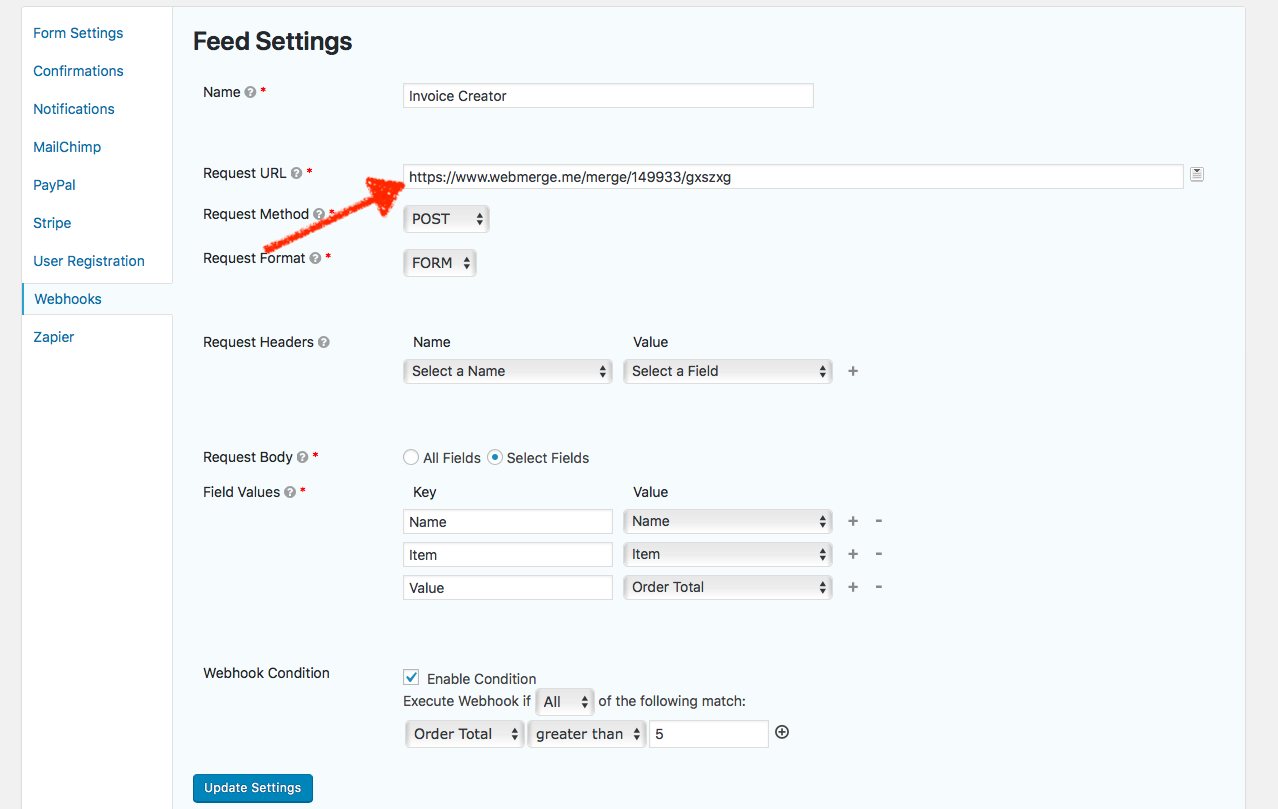

Finally, go back to your trigger app—Gravity Forms in our case—and paste the webhook URL in Gravity Forms' URL field. You may also be able to set the correct request method and the specific field values to ensure only the data you want is sent, and is shared with the same variable names as the receiving app uses. Save the settings, and you're good to go.

The next time someone fills out our form that Bob ordered 10.00 of paper, Gravity Forms will send the data to WebMerge's URL as https://www.webmerge.me/merge/149933/gxszxg?Name=Bob&Item=Paper&Value=10.00 and WebMerge will turn that into a complete invoice.

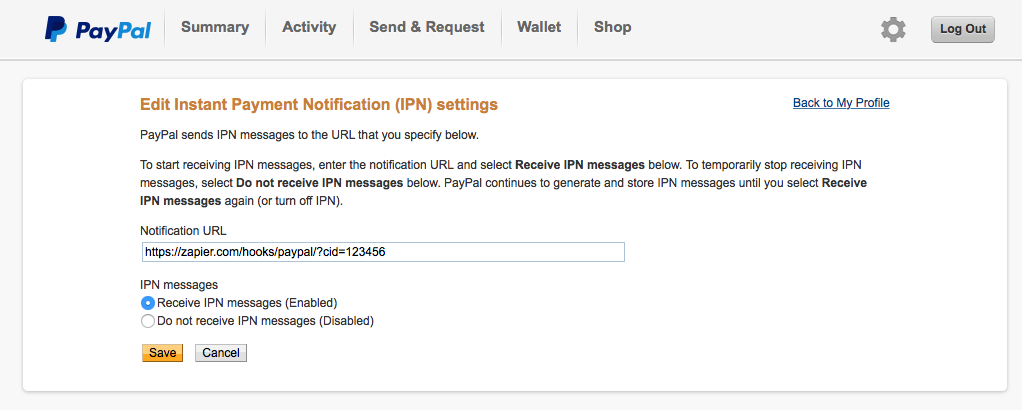

Once you start using webhooks, you'll notice them (or similar links) everywhere, in places you never thought they'd show up. PayPal, for instance, uses Instant Payment Notifications or IPNs to send notifications whenever you receive a payment. Have an app that you'd like to do something whenever you get a PayPal payment? Add its webhooks URL to PayPal's IPN settings and that app will get a message the next time you get money.

Or take Twimlets, Twilio's simple apps to forward calls, record voicemail messages, start a conference call, and more. To, say, forward a call, you'll add a familiar, webhook-style Twimlet address like http://twimlets.com/forward?PhoneNumber=415-555-1212 to your Twilio phone number settings. Want to build your own phone-powered app, or notify another app when a new call comes in? Put your webhook URL in Twilio's settings instead.

They might go by different names, but once you notice places where apps offer to send notifications to a unique link, you'll often have found somewhere else webhooks can work. Now that you know how to use webhooks, you can use them to make software do whatever you want.

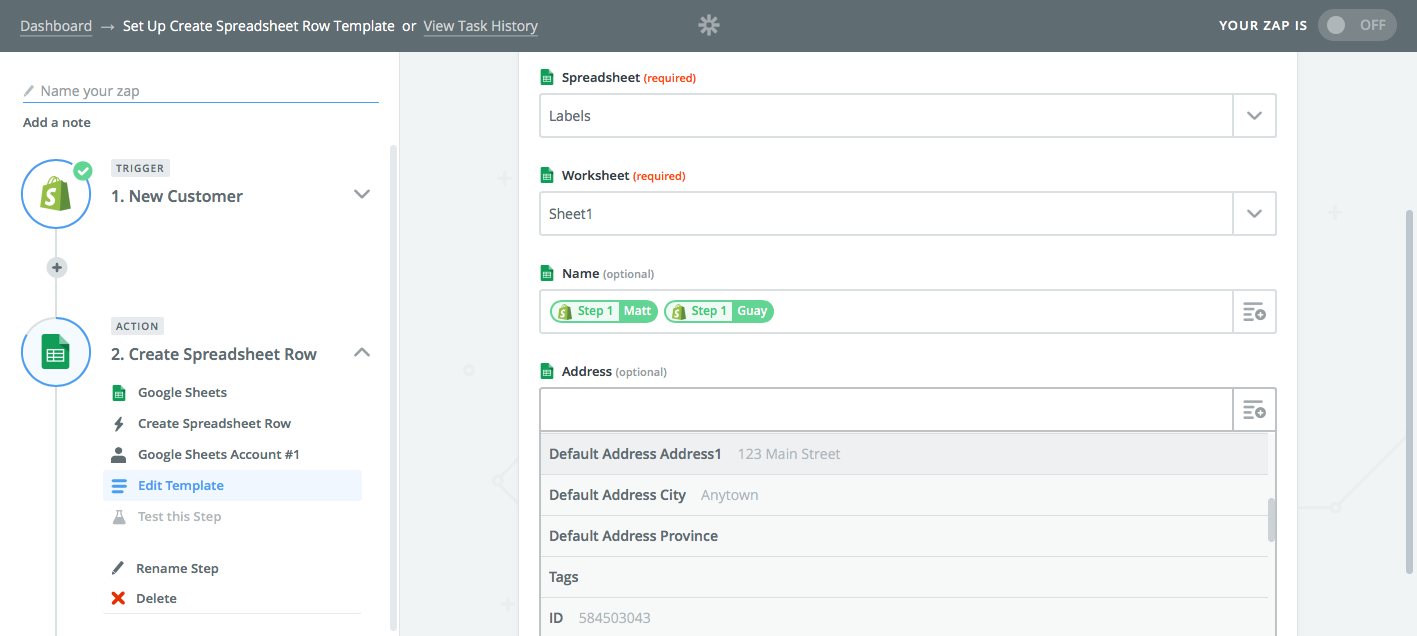

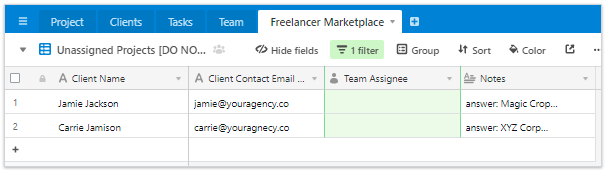

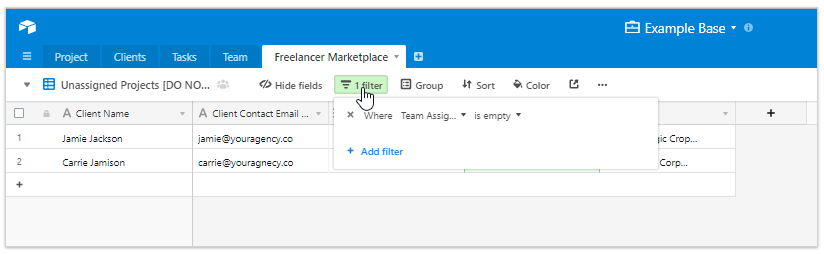

Use Webhooks in Any App with Zapier

Have an app that can send or receive data with webhooks, and want to connect it to another app that doesn't seem to work with webhooks? Zapier can help. With over a thousand connected apps, there's a good chance the app you want to use works with Zapier. You can then have Zapier handle the webhooks part to connect both of your apps.

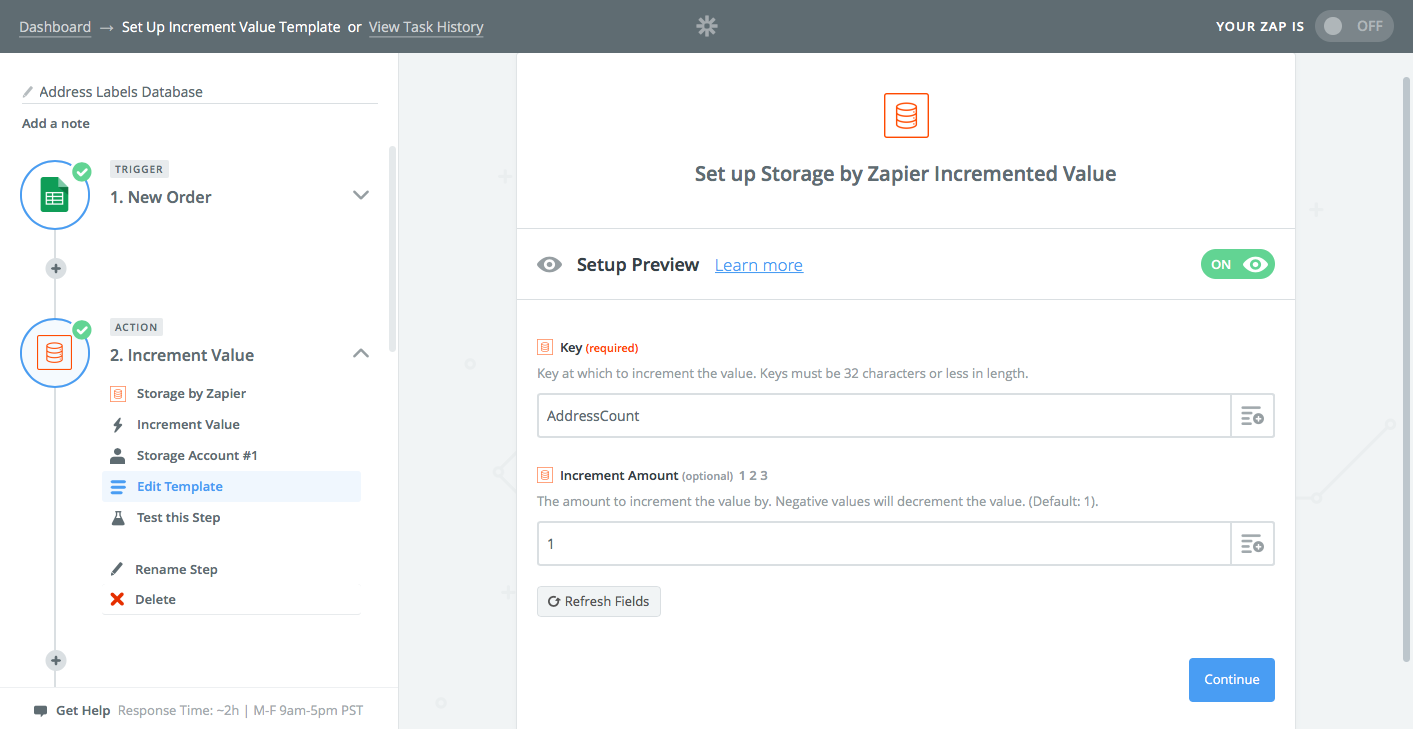

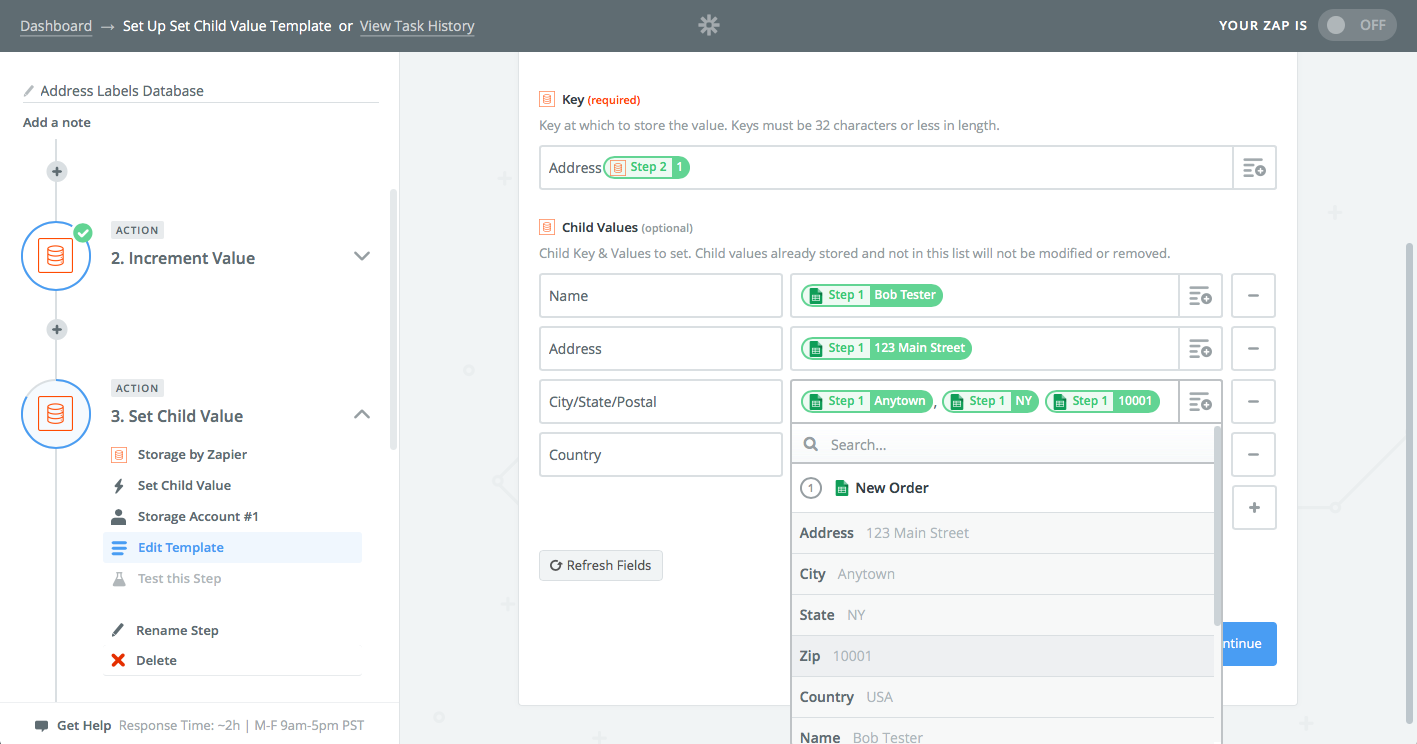

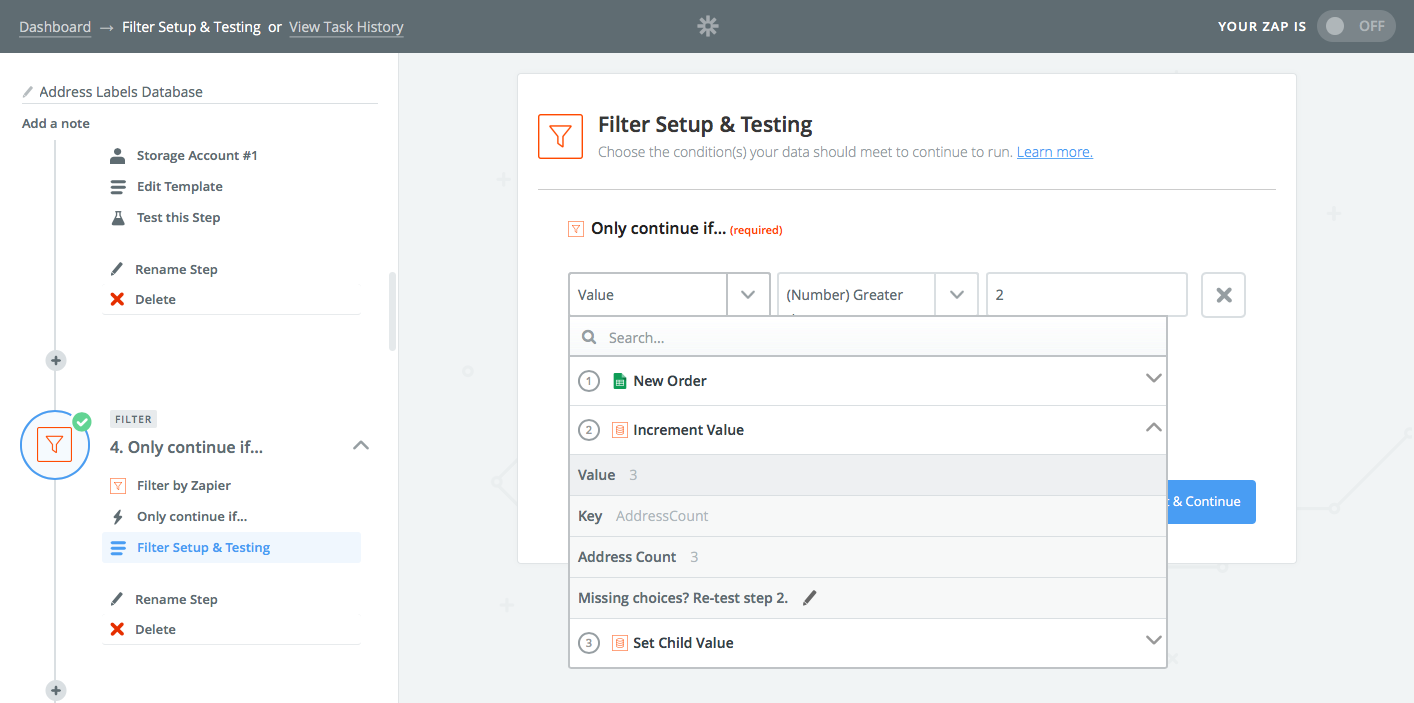

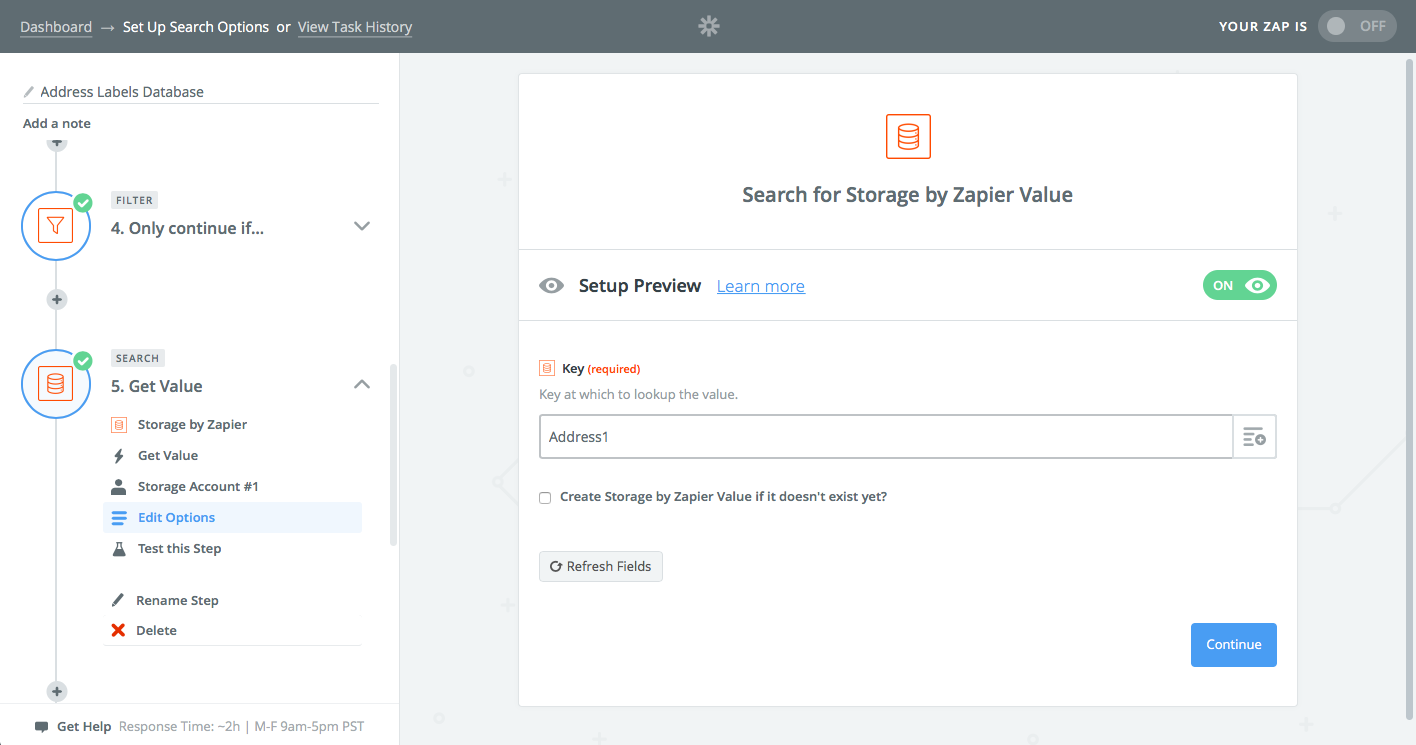

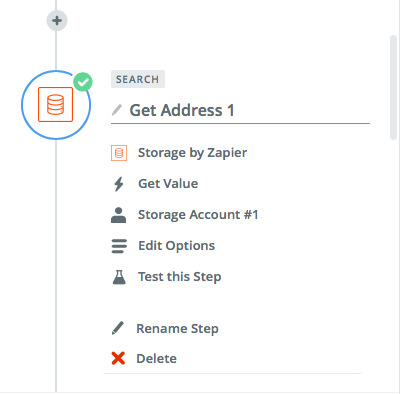

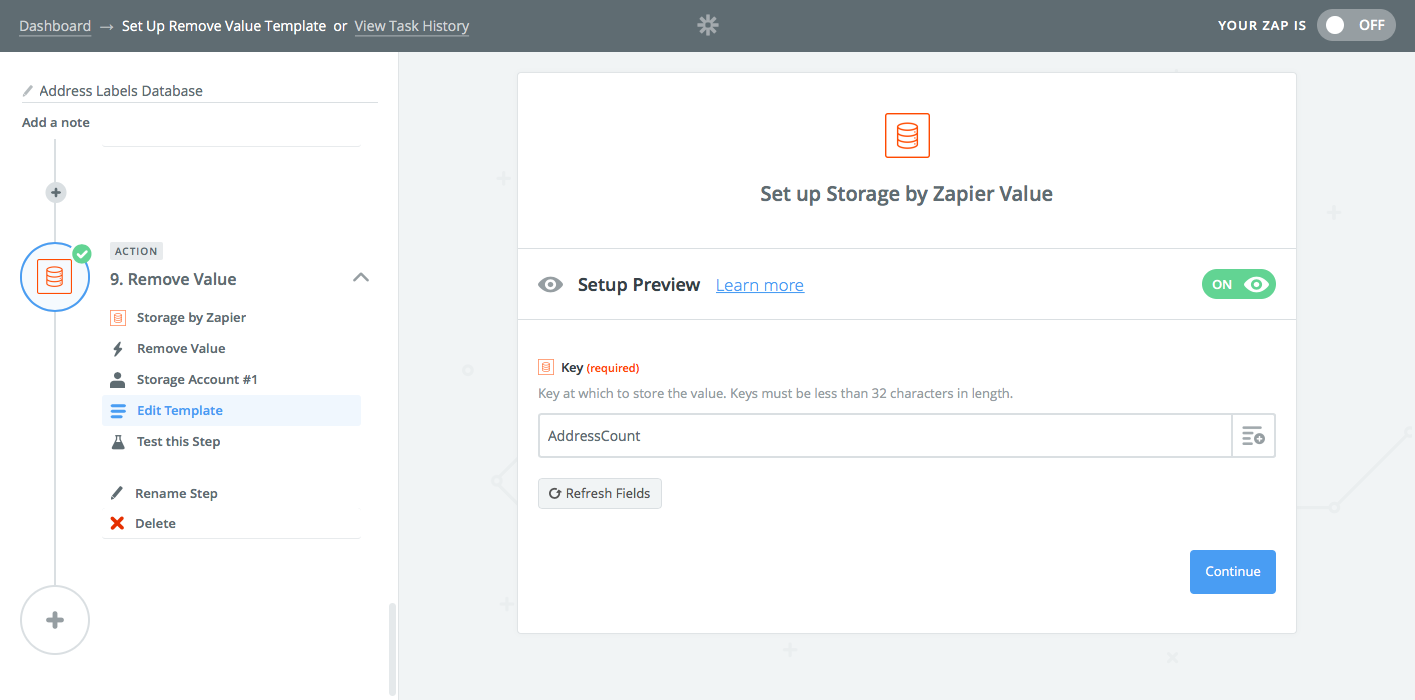

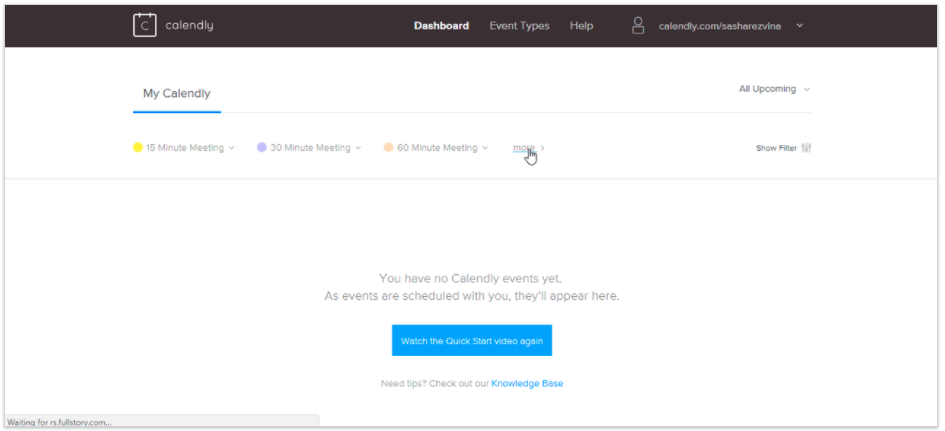

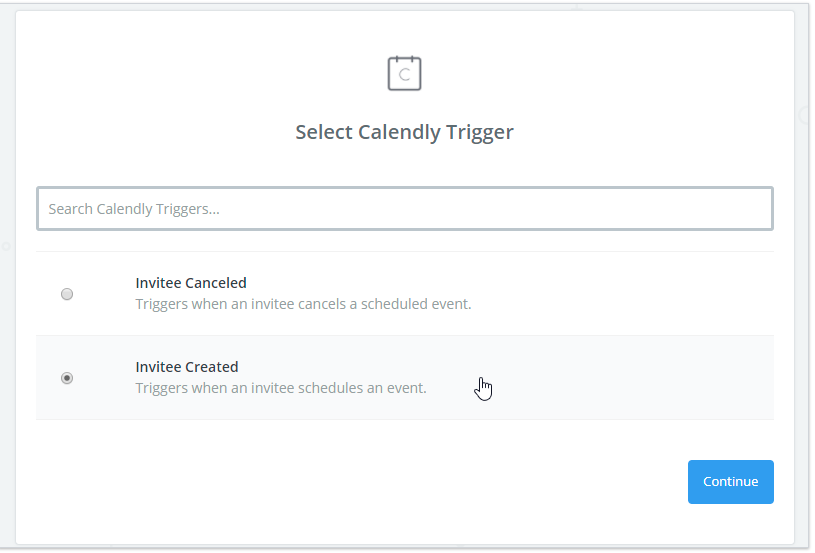

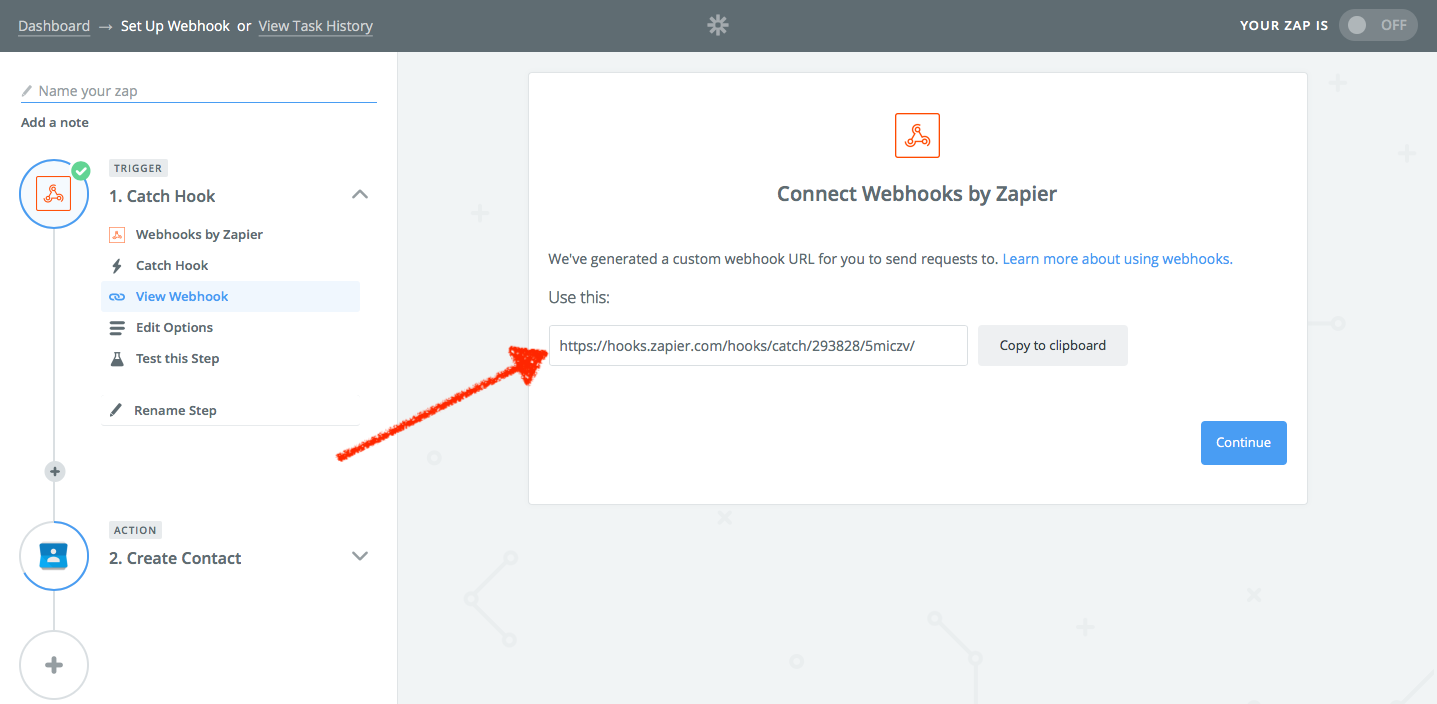

Say you have an app that can share data to a webhooks URL. To connect it to other apps, you'll make a new Zap—what we call Zapier's automated app workflows—and choose Zapier's Webhooks app as the trigger app. Select Catch Hook, which can receive a GET, POST, or PUT request from another app. Zapier will give you a unique webhooks URL—copy that, then add it to your app's webhooks URL field in its settings.

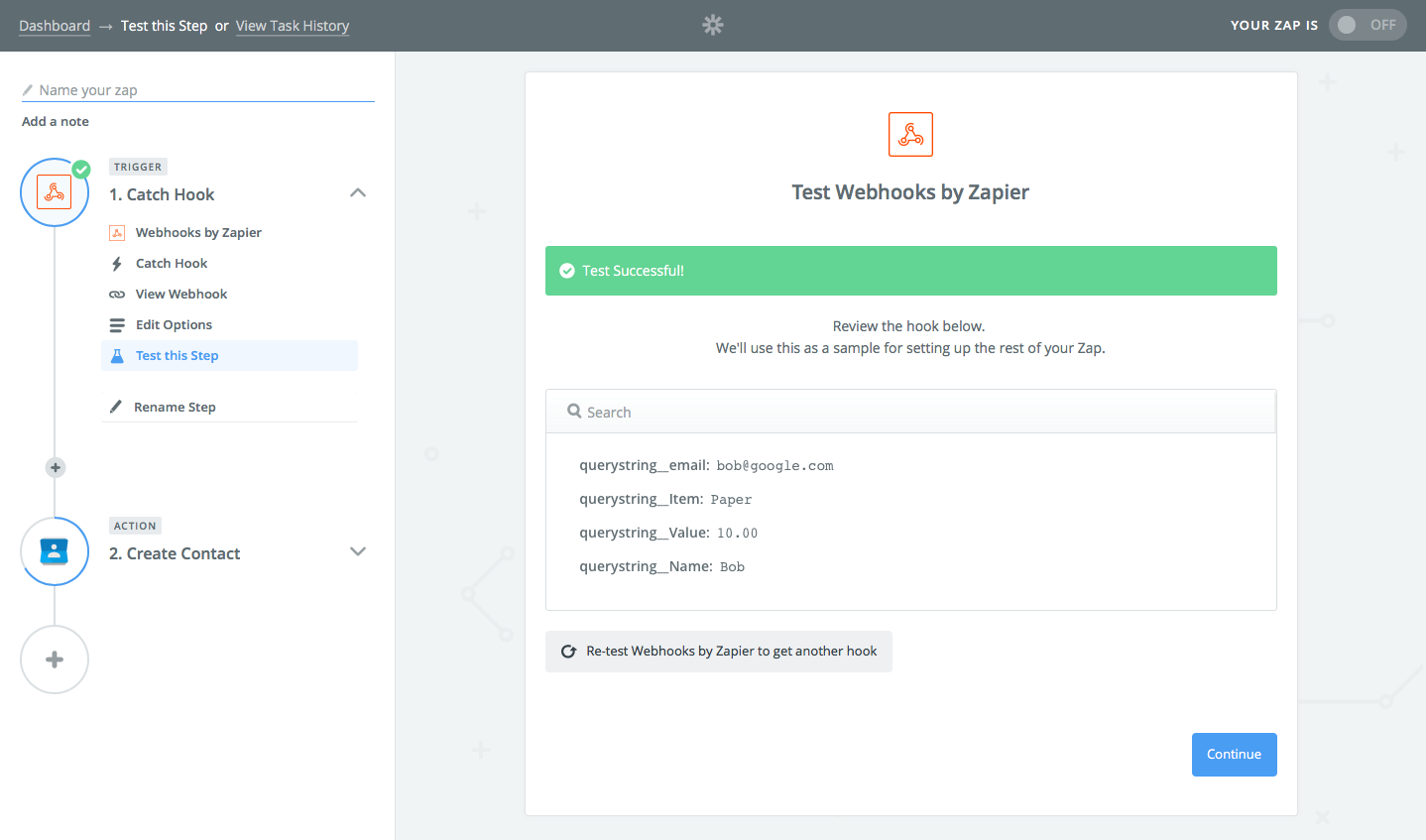

Then have your app test the URL, or perhaps just add a new item (a new form entry, contact, or whatever thing your app makes) to have your app send the data to the webhook. Test the webhook in Zapier, and you'll see data from the webhook listed in Zapier.

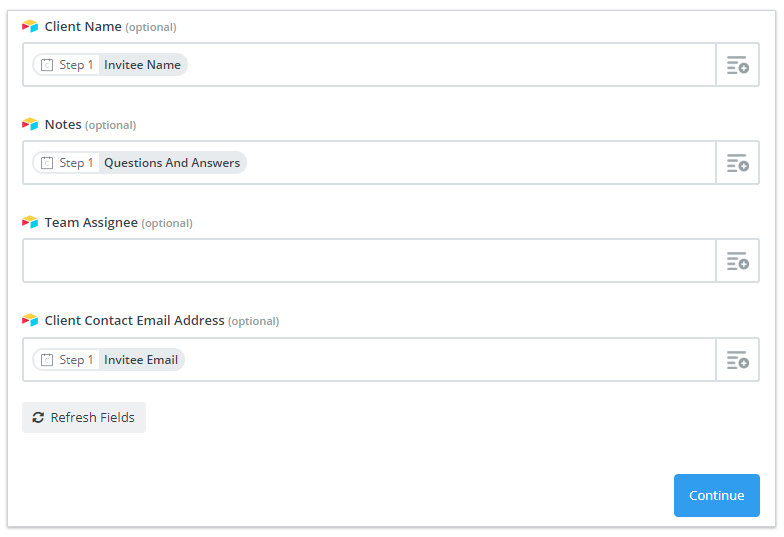

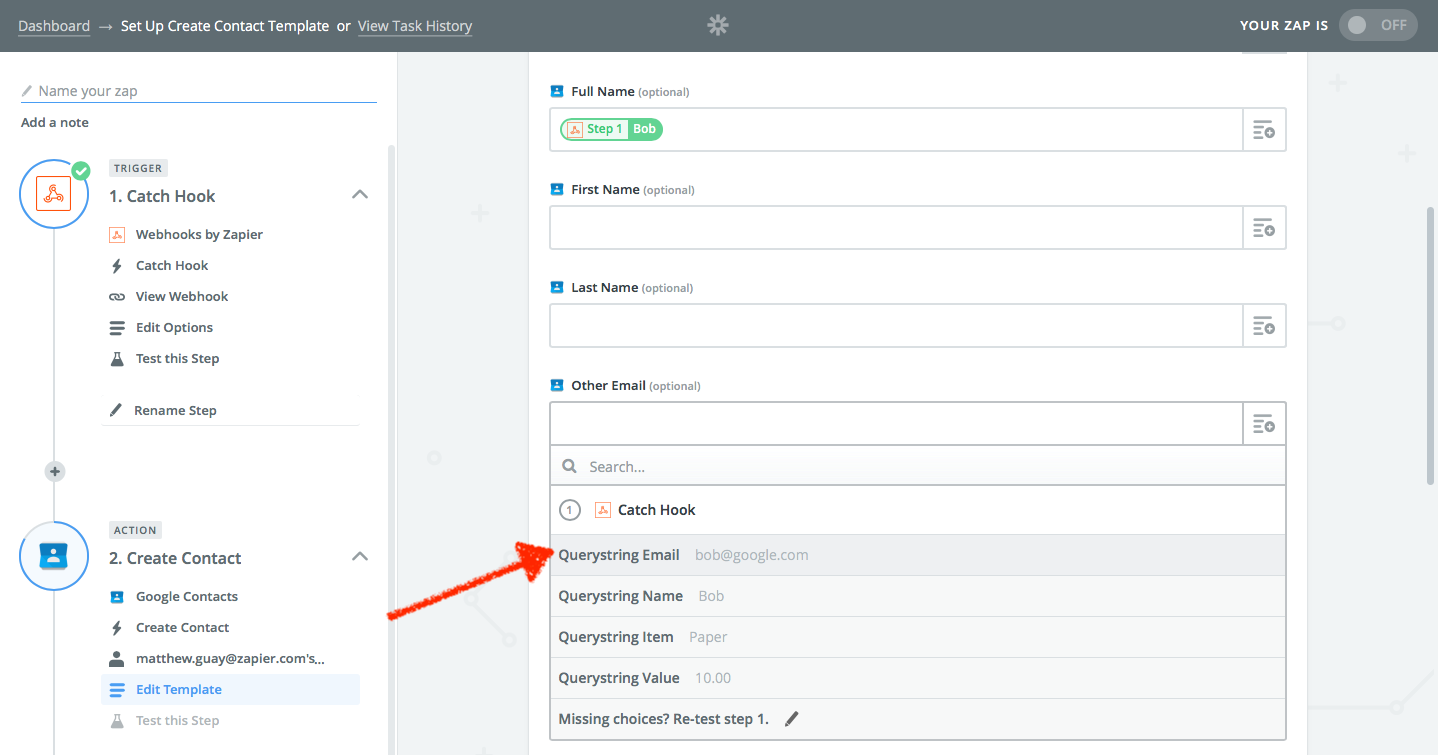

Now you can use that in another app. Select the action app—the app you want to send data to. You'll see form fields to add data to that app. Click the + icon on the right to select the data from your webhook you want to send to the other app. Test and turn on the Zap, and next time your trigger app sends data to the webhook, Zapier will automatically add it to the action app you selected.

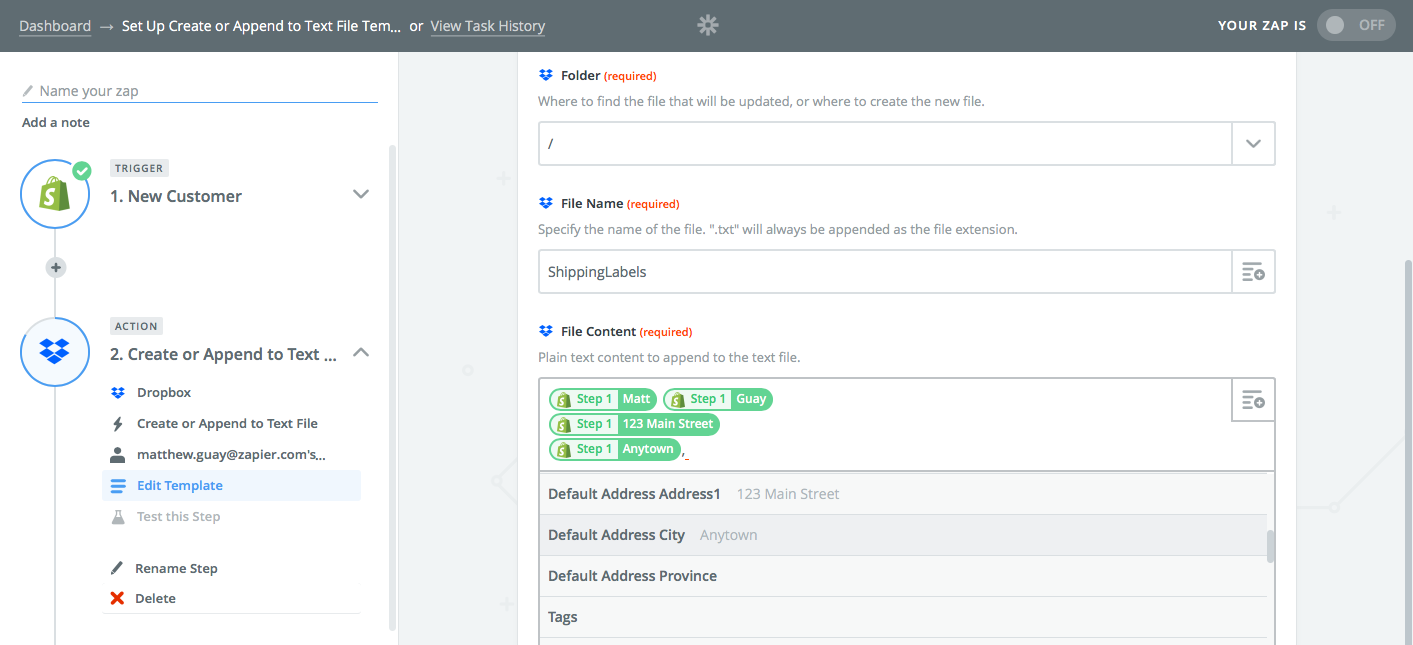

The reverse works as well. Want to send data from one app to another via webhooks? Zapier can turn the data from the trigger app into a serialized list and send it to any webhooks URL you want.

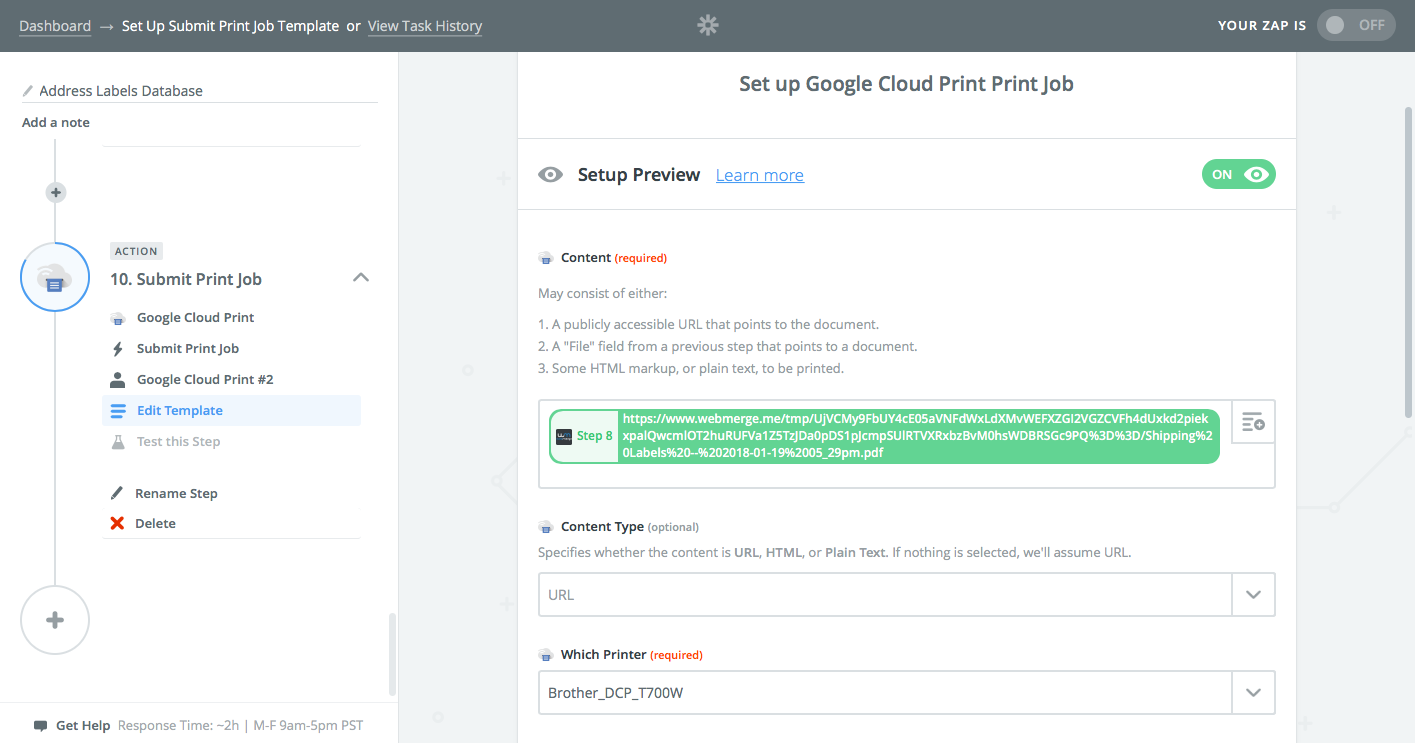

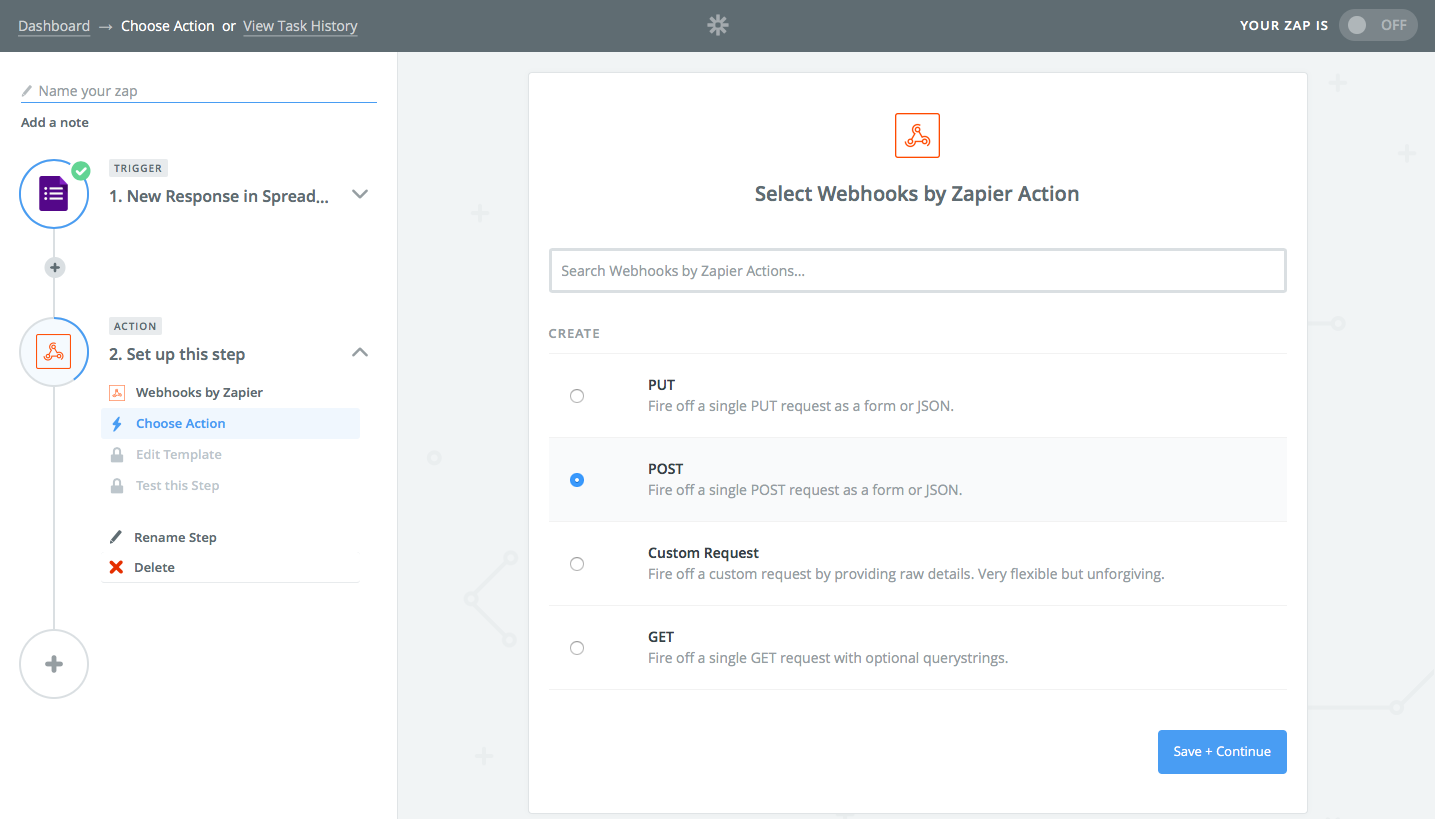

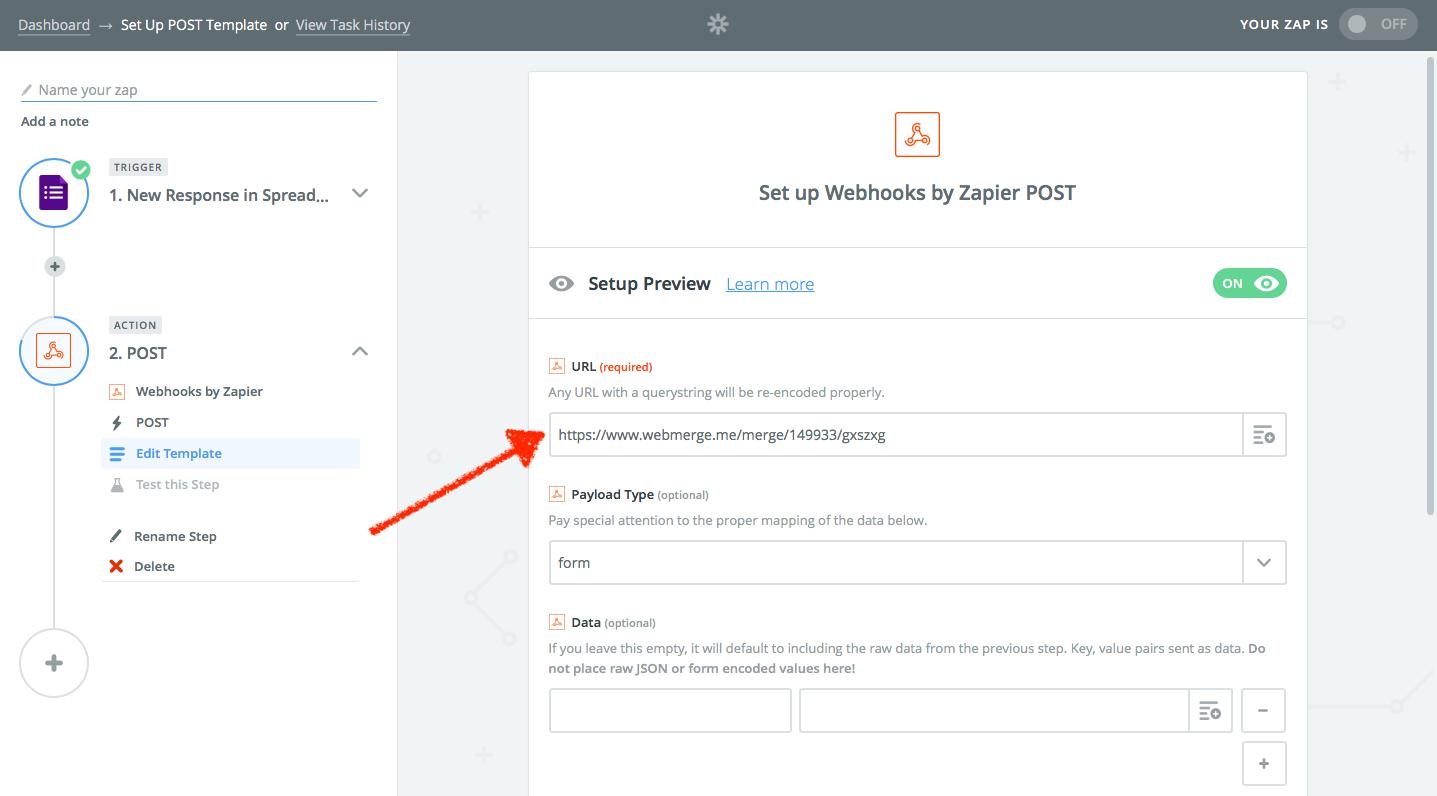

First, select the trigger app you want to send data from, and set it up in Zapier as normal. Then select Webhooks as the action app, and choose how you want to send the data (POST is typically the best option for most webhook integrations).

Finally, paste the webhooks URL from the app you want to receive the data into the URL field in Zapier's webhook settings. You can choose how to serialize the data (form or JSON are typically best). Zapier will then automatically send all of the data from your trigger app to the webhook—or you can set the specific data variables from the Data fields below.

Turn on the Zap, and whenever something new happens in your trigger app, Zapier will copy the data and send it to your other app's webhooks URL.

Ready to automate your webhook work with Zapier? Check out Zapier's webhook integrations or use one of these popular Zap templates to get started quickly:

Time to Start Using Webhooks

Ok, you've got this. Armed with your newfound knowledge about webhooks and their confusing terminology, you're ready to start using them in your work. Poke around your favorite web apps' advanced settings and see if any of them support webhooks. Think through how you could use them—then give it a shot.

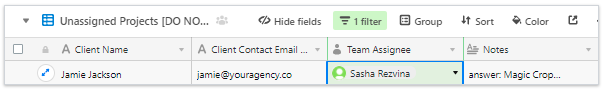

Or, check out our How Real People Use Webhooks guide for stories from four teams who use Webhooks with Zapier to manage projects, store data, schedule social media, connect in-house apps, and more. They're great inspiration for ways you can put webhooks to work for you.

And bookmark this article. Next time you read something about a GET request needing to make an HTTP callback, or see a URL with ?name=bob&value=10 and such at the end, you'll know what it actually means.

Webhooks Glossary: Common Terms and Definitions

- Webhook: A serialized message sent from one application to another's unique URL over the web.

- Webhook URL: The link where an application will receive webhook data from another app.

- HTTP: Hypertext Transfer Protocol, the communication standard that enables computers to transfer data; the protocol that powers the world wide web.

- Hook: A software function that runs when a specific event happens.

- Response or Callback: The data sent from the receiving application back to the sending application, often including HTTP status codes to let the application know the data was received.

- Pipe: A Unix command line method to route data from one application to another; the closest desktop equivalent to webhooks.

- Ping: To contact a computer over a network, see if it's active, and optionally send data to it.

- GET: An HTTP request to ask for data from a computer—what your browser uses to ask for a webpage when you enter an address in your browser. GET requests are the simplest way to send data to a webhook URL by appending the data to the end of the URL in form encoded serialization.

- POST: An HTTP request to submit data to a computer—what your browser uses to send text you type in a form back to a website. POST requests are the most common way software send data to a webhook URL, and POST requests can transfer far more data than a GET request.

- PUT: An HTTP request to submit data to a computer for a specific resource, typically used to update data. PUT requests can be used to send data to a webhook URL, though the data will need to include the name or location of the resource to be added or updated (so a POST request is best to add a new contact to an address book app, say; a PUT request would be used to update the contact as long as you know the existing contact's info).

- Serialized: Data organized in a list, typically separated by commas.

- Form Encoded: The most way basic to serialize data used with GET HTTP requests to send form data back to a server; data is separated with ampersands. Example:

Customer=bob&value=10.00&item=paper - JSON: JavaScript Object Notation, a standard to serialize data with commas, groups with curly brackets to simplify sharing multiple values at once. The most common way to serialize webhook data, especially with POST requests. Example:

{"customer": "Bob", "value": 10.00, "item": "paper"} - XML: eXtensible Markup Language, the data formatting standard that forms the basis behind HTML and other common online documents, with data separated by tags designated by greater than and less than symbols. Example:

<data><customer>Bob</customer><value>10.00</value><item>paper</item></data> - Catch: To listen for new data sent to a webhook URL, typically then to process and use the data in the receiving app.

- Poll: To ping a URL and ask for new data, similar to refreshing a page in your browser. The older way applications would get data from each other before webhooks.

- Payload or Body: The data sent from one application to a webhook URL for another application to catch, typically in serialized format. Can also include HTTP headers for authentication with POST and PUT requests.

- Header: Additional data included with an HTTP request to identify the sender and their location, include authentication data or security signatures, and other related data.

source https://zapier.com/blog/what-are-webhooks/